Project narrative

The Hybrid Bodies project brought together cardiologist Dr Heather Ross, philosopher Prof Margrit Shildrick, transplant psychiatrist Dr Susan Abbey, social scientist Patricia McKeever, specialist nurse Enza de Luca and sociologist Dr Jennifer Poole and four artists. Alexa Wright (GB) Catherine Richards (CA) Ingrid Bachmann (CA) and Andrew Carnie (GB). We created works in a variety of media, including video, sound, interactive installation, drawing and photography, to explore the personal experiences of heart recipients and of donor families. Two more Canadian artists, Emily Jan and Dana Dal Bo, joined the team at a later stage, along with art historian Tammer El-Sheikh and curator Hannah Redler Hawes.

The original project was initiated in Toronto by Ross, Shildrick and McKeever, when Ross observed that her patients were not responding well emotionally and psychologically to transplanted organs, even though the organs were performing well physically. In 2006, along with Andrew Carnie, I was invited to participate in the project for knowledge translation purposes, and I invited Canadian artist Ingrid Bachmann to join. Over the next four years our role became more significant as we gained the trust of the rest of the team. Drawing on my previous experience of working with scientists, I was able to bring the group closer together by initiating a series of in-progress exhibitions. While each artist worked independently, making our own works from the same research material, there was frequent dialogue. My role also involved fundraising, overall development of the creative aspect of the project, organising opportunities for dissemination and promotion of the project, and production of works in a range of media, including interactive audio installation, video, photography and robotics (the latter is still in progress).

In the cardiac unit at Toronto General Hospital, an international, interdisciplinary team of medical practitioners, social scientists, artists and a philosopher set out to investigate the phenomenological impact of heart transplant for recipients and donor families. Based on hundreds of hours of video interviews, our project explored the disruption to organ recipients’ sense of self as a result of their bodily transformations, and the trauma induced by enforced anonymity between recipients and donor families.

To give a voice and emotional register to the beneficiaries or subjects, I developed artworks across a range of media, including photography and sound. Early works, such as Heart of the Matter (2014), an interactive audio installation first exhibited at the Phi Centre, Montreal, interweave narratives of physical and emotional heartbreak. Still Live (2019) – first shown at Concordia University, Montreal, in 2019 – is a later series of photographs that draws on imagery from 16thand 17th-century Dutch vanitas paintings to explore complex themes such as living and dying, proximity and distance, loss and rejuvenation. Cut (2018 –19), first exhibited at Winchester Gallery in 2018, is a series of seven photographs and Not Gone, Not Forgotten (2019), a two-screen video piece, in which fragments of one family are literally collided with another.

The ongoing artistic dissemination of the team’s findings enhanced public and professional understanding of the issues involved in organ donation. For example, following a workshop I organised in Winchester in 2018, Katie Morley, transplant coordinator at Royal Papworth Hospital, Cambridge commented: “I now plan to extend our educational programme to include elements of the issues/work/ideas discussed during this artist-led workshop. I will take away ideas to be used with staff and patients to try to encourage others to think and express themselves in a non-medical fashion. From a personal perspective I think there are elements of the art displayed that would help recipients of transplant to cope/understand the impact transplant has had on their lives.”

The method of coordination of a range of activities, exhibitions, workshops and discussion led to meaningful exchanges that were then reconciled into the subsequent iterations of the work. These methods, which are sometimes familiar within health-community art commissions, were sustained by this long-term engagement.

The AHRC Research Network Award took up the discussion that had been taking place within the group. UK artists were asked to participate in the team’s network activities, which created new international links between researchers working across a range of disciplines. The resulting process of work-in-progress exhibitions and events acted as catalysts to facilitate knowledge exchange at the highest level internationally, enabling the team to share and examine their working practices with other artists, curators and museum and gallery professionals, enhancing the understanding of interdisciplinary practice in the arts and building new and ongoing interdisciplinary relationships. These events fostered working relationships between existing members of the team and new UK collaborators and have led to invitations to present at future interdisciplinary events.

Realisation of the work involved:

- Production of artworks in a variety of media including photography, video installation, interactive audio installation.

- Long-term, international collaboration between artists and scientists to exchange expertise via programmed workshops, seminars and work-in-progress exhibitions.

- Data-gathering in the form of video interviews with organ recipients and with donor families and visual analysis of this data.

- Exhibitions, symposia, interdisciplinary workshops, articles and books.

Production narrative

The project was carried out in two phases, The Process of Incorporating a Transplanted Heart (2007–14), which looked at the experience of heart recipients, and Gifting Life: Embodiment, Affect, Anonymity and Kinship (2014-20), a study of donor family experience. In both phases the primary data consisted of video footage of private, semi-structured, open-ended interviews. Nearly 100 hours of footage was analysed in detail by the whole team to try to understand the discrepancy between each interviewee’s verbal responses and their body language. Due to ethical constraints the material could only be viewed in a highly controlled setting at Toronto General Hospital. So we made annual or bi-annual visits to Toronto throughout the project to study this data and meet face to face with the scientists.

Our initial methodology included reviewing the data, discussions with the medical team and developing and prototyping artworks based on research material. A number of work-in-progress exhibitions enabled us to evaluate the potential impact of the works and to gauge audience response to the issues addressed by the project and the use of visual art to communicate organ donor families’ experiences.

During the first phase of the project, in response to the recipient interviews I created Heart of the Matter (2014) and Cadenza (2014), the two submitted pieces that were first exhibited in 2014. Heart of the Matter explores the intimacy of the transplant process and the blurring of boundaries between self and other that occurs as a consequence of integrating the transplanted organ, particularly the heart with all its cultural symbolism. Using edited sections of interviews, alongside transcriptions of my own interviews with heart recipients and with people who experienced an emotional exchange of hearts in intimate relationships, I created scripts that were then voiced by actors. In the Heart of the Matter installation, the voices emerge from a series of felt jackets, activated as visitors approach. I worked with Michael Mersereau, a programmer, to facilitate the interactivity. Heart of the Matter was first shown as a finished work at the Phi Centre in Montreal. However, the installation was modified in 2016 for an exhibition at KKW in Leipzig. Steel stands were made for the jackets and the audio component was rerecorded in German. Heart of the Matter has subsequently been shown a number of times. In all contexts the work has provoked dialogue and speculation about what it means to live with someone else’s heart.

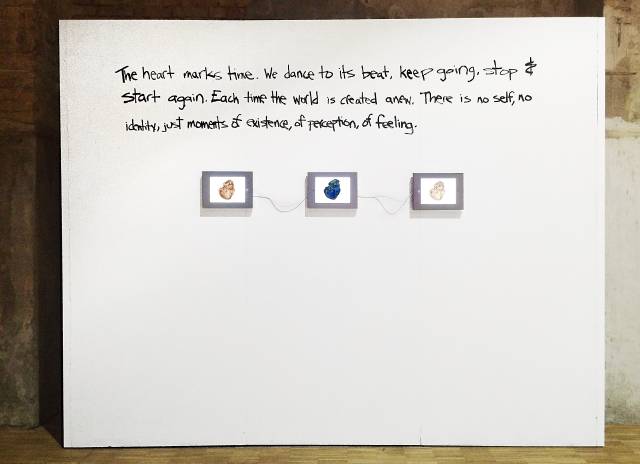

Cadenza (2014) was also made for the first stage and for Phi, where it was shown as a triptych. This work explores the strength and fragility of the human body via a reanimated image of an explanted heart. It was remade for exhibition at London Gallery West in 2017 as a single monitor embedded in a plinth with an audio element (excerpted from Nina Simone’s Feeling Good).

In response to the second phase of the project, I created Cut (2018–19) and Not Gone Not Forgotten (2018), both of which explore the relationship between donor family and recipient by visually inserting fragments of a body into a different domestic interior. Not Gone Not Forgotten also includes quotes from donor family interviews. Also the photo series, Still Live (2019). These works were informed by interviews conducted by the AHRC-funded team, and by my own interviews carried out with two donor families in the UK.

Themes that recurred in many interviews were: distress at not knowing who the organ recipient was or where they were, but also anxiety over what kind of person they might be and whether they would be “appropriate”. Research showed that donor families are often traumatised by not knowing where their loved one’s heart has gone, and recipients are traumatised by not knowing whose heart is keeping them alive.

| Creators | Wright, A. |

|---|---|

| Description | In 2017, Wright was awarded an AHRC Research Network grant to bring an interdisciplinary study into the effects of heart transplantation on donors’ families that originated in Canada to the UK for the first time. The Network grant enabled Wright to develop a wider interdisciplinary network, enabling further insights into the effects of heart transplantation on recipients and donor families. Key questions asked include: How might art act as a bridge between the experience of heart-donor families and medical professionals? What forms and methods of artistic practice are most appropriate in this context? What are the implications of considering organ transplant as a form of inter-corporeality? Through exhibitions, symposia, workshops and other activities, the project shows that as well as blurring the boundaries between self and other, organ transplantation has deep implications for our understanding of the relation between death and “staying alive”. Recipients of donor organs often find the experience of surviving an otherwise certain death is fraught with complex emotions about the relationship between the self and the now dead other, while donor families understandably wish to see the donor living on in another. Through art, Wright and collaborators found that they could tackle these emotive aspects of transplantation that resist verbal or textual communication in new and accessible ways. Comparison between Canada and UK transplant regulations led to new insights on future policy. |

| Portfolio items | Messy entanglements: research assemblages in heart transplantation discourses and practices |

| Hybrid Bodies at KKW | |

| Hybrid Bodies | |

| Heart of the Matter | |

| Cadenza | |

| BBC Radio 4: interview and excerpts of audio from Heart of the Matter in Print Me A new Body programme | |

| The Heart Project (exhibition and symposium) | |

| Cut | |

| Not Gone Not Forgotten | |

| Still Live | |

| Heart of the Matter - The Flesh of the World | |

| Heart of the Matter PHI exhibition | |

| Heart of the Matter - Crafting Anatomies | |

| Hybrid Bodies laser talk | |

| When Words Fail, an interdisciplinary investigation into the phenomenological effects of heart transplantation | |

| Hybrid Bodies Chiasma Exhibition | |

| Sutured Selves, Remapping the Boundaries between our bodies, our selves and our kin | |

| Art/Sci Nexus, 9 Evenings Revisited | |

| Papworth Hospital Heart Transplant Recipient Workshop | |

| Parallax, a story in two parts | |

| Hybrid Minds, Hybrid Bodies | |

| Object Stories | |

| Donor Family and Recipient Anonymity: Time for Change | |

| Year | 2014 |

| Publisher | University of Westminster |

| Web address (URL) | http://www.hybridbodiesproject.com |

| Keywords | collaboration; interdisciplinary; art science |

| CREAM Portfolio | |

| Funder | AHRC (Arts & Humanities Research Council) |

| Arts Council England | |

| Digital Object Identifier (DOI) | https://doi.org/10.34737/qqw60 |