Research insights

As an artist investigating various theoretical issues via my practice, this project tends towards several conclusions. First, that post-conceptual painting is possible without it being a humanist “return to Painting”. Rather, it accords with conceptual art’s destabilising of traditional mediums such as painting and their self-validating assumed notions of autonomy. Almost any material can be used to realise ideas and I conclude that post-conceptual painting is not real painting, but a representation of painting: a stand-in. Generic painting that results in a type of object. It could be said that post-conceptual painters “nominate” objects to assume the place of painting; in the process the pictorial aspect of painting is jettisoned, while its “objecthood” is promoted. What interests me, however, is the crossover point where the work is both object and picture – a possibility that generic painting, as simply a set of signs, is unable to contain.

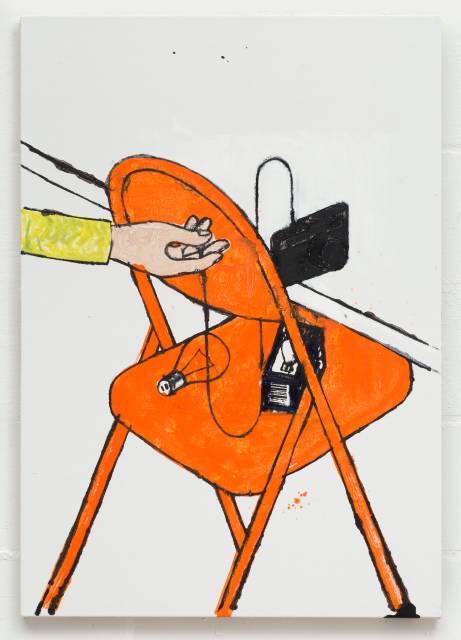

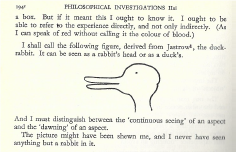

Let’s take as an example, How to Change a Lightbulb – Orange Chair (2016), a painting of a folding chair that is a type of still life. Its illustrational simplicity contrasts with the materiality of its crudely painted surface, manifesting an objecthood that cannot be seen while viewing it as a picture. The perception of this image gets to the core of my own interest in presence and absence, a theme I have used repeatedly in the past. Just as Ludwig Wittgenstein’s famous duck/rabbit diagram highlights that both rabbit and duck cannot be seen simultaneously – one is always absent in the other’s presence – to look at a painting and see an object is to not see its pictorial dimension, while to see it pictorially is to not see its objecthood. The motif in this case can be said to be meta because it refers to the way a picture is seen as a picture or (painting) object, the way consciousness switches between “there” and “not there”.

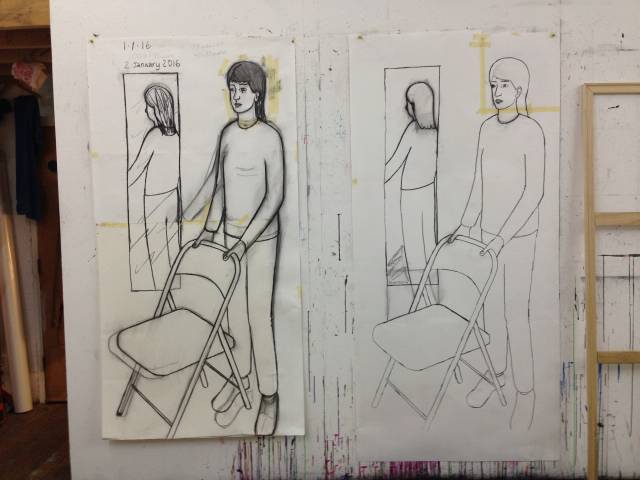

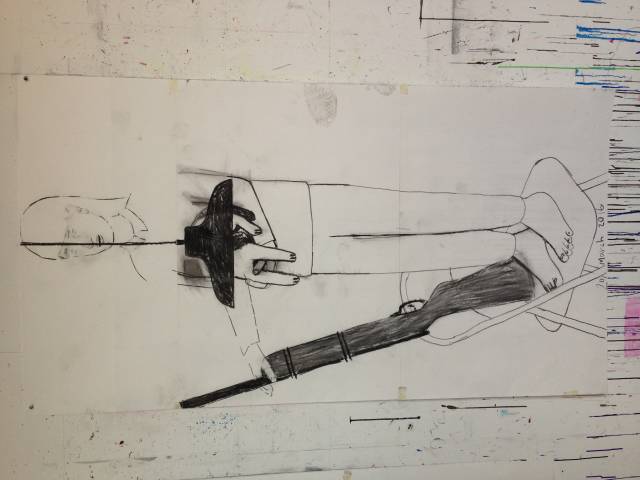

Generic painting could not offer me the potential of the “there” and “not there” duality, because it dismisses a pictorial dimension. But my continued fascination with painting has led me to rate its pictorial qualities over its objecthood. And try as I might to simplify, reducing style to the anti- or nonstyle of a how-to manual, complexity and ambiguity are stubbornly standing their ground. In Looking Through a Hole (2016), for example, the picture that came to define the complete body of work, an androgynous figure is hiding, or hunting, or both. Or are they simply looking through a hole? A hole which reappears above the head like a cartoon thought bubble, depicting what is seen (in the head of the figure) through the hole. Or is it an actual hole in the painting ground? The central character was devised as a reflection on introversion and shyness, corresponding to how we look at pictures, in so far as we see them, but are not reciprocally seen.

The rifle, which clearly has a metaphorical and dreamlike existence as an extension of the figure’s shoulder, provokes a question: what do we do when we have found what we are looking for, and once we have seen it? Like a hunter, a picture-maker has to capture, and not necessarily with due ethical care; in fact, the two are often incompatible. The experience of Looking Through a Hole, with its dream-like imagery, is dependent on visual metaphor, in so far as an interpretation cannot be fixed by either author or viewer. The metaphor creates a resemblance by implication and does not have a literal meaning or specific content. As such, the compilation of elements that form the picture may (or may not, dependent upon a lack in either the viewer or the work) be experienced like the joke form as discussed in psychoanalysis – by affect and not logic.

Which brings me back to Peter Osborne’s phrase “the experience of meaning”. The pleasure I find in looking at (and making) art is definitely an “experience”. For me, art is an experience, in the face of which you become aware that some kind of meaning is happening. Conceptual art and minimalism have sought to explain art in relation to the rational, and most of the art I am interested in does indeed have a rational side. But the part I am most interested in cannot be explained rationally – namely the aesthetic, which is often diminished by the idea of rationality being superior. In my search for a contemporary milieu for painting, I have pared back my practice to an elementary set of pictures, yet I am unable to eliminate a desire for complexity: allusion, metaphor, ambiguity – and, of course, humour – persist of their own accord.

| Creators | Cumberland, S. |

|---|---|

| Description | The research interrogates post-conceptual painting and repositions it as picture making. Stepping outside the parameters of painting as a medium, drawing on historical references and investigations of contemporary psychoanalysis, |

| Portfolio items | Sensible Signs: Pictures and Not Painting After Conceptual Art |

| The Painting Show | |

| Handmade Colour Pictures | |

| Year | 2016 |

| Publisher | University of Westminster |

| Keywords | Paintings, Postconceptual, Pictures. |

| CREAM Portfolio | |

| Digital Object Identifier (DOI) | https://doi.org/10.34737/qqqz8 |