Project narrative

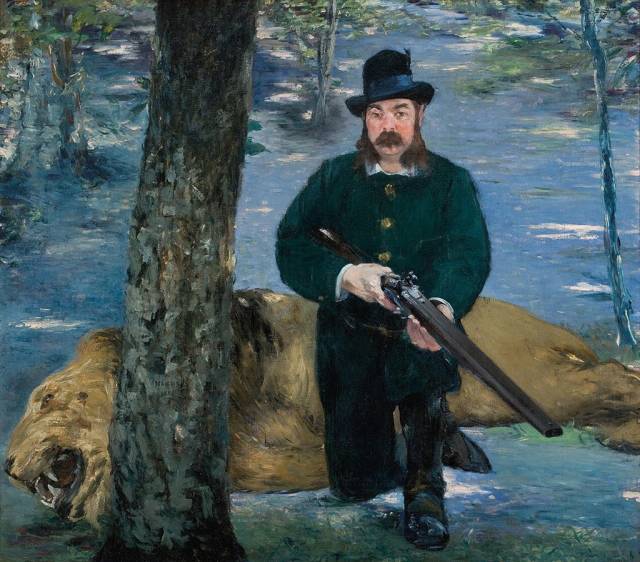

Diego Velazquez and Edouard Manet made hunting portraits – Cardinal Infante-Ferdinand of Austria, in Hunting Dress (1632), Philip IV in Hunting Dress (1632) and Prince Baltasar Carlos, in Hunting Dress (1635) by Velazquez are all in the Prado; Manet’s Monsieur Pertuiset, the Lion Hunter (1881) is in Sao Paulo Museum of Art – and I took these works as starting points. The notion of the hunt interested me because of its parallels with making pictures by trapping images. After all, the picture is an image held in place – captured – by medium or media. Hunting also prioritises looking, a fundamental of visual pleasure.

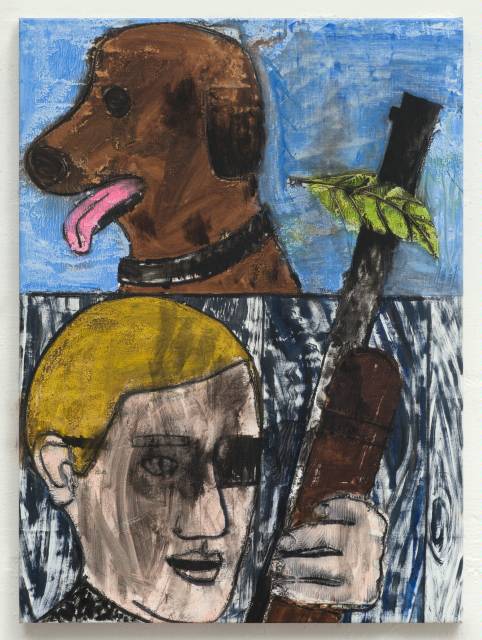

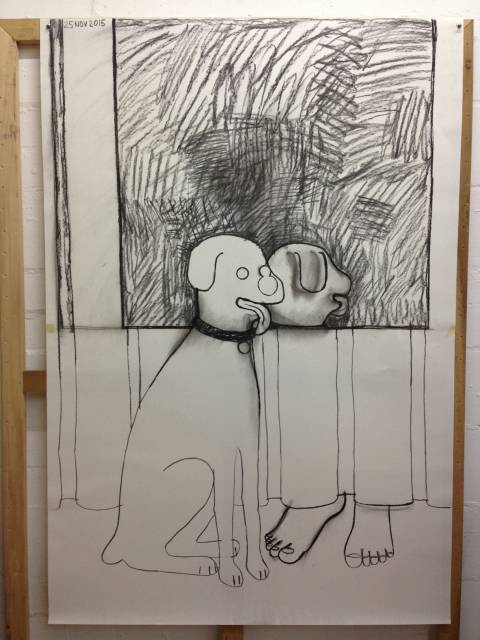

My pictures include what was for me a new inventory of motifs, including dogs, guns, cameras, leaves and chairs to produce what the exhibition publicity described as “a narrative mystery”. The pictures are not so much portraits as frozen narratives, the experience of which emphasises the importance of questioning rather than specific interpretation. The questions I was asking focused on the ambiguity of the picture structure: how we read the pictorial location of each motif and the relations between them; relations that are both spatial and part of a subjectively constructed narrative. For example, in Brown Dog & Man with Gun (2015) we might ask: where is the dog in relation to the fence, gun and leaf and what is the relationship between the dog and the person? What do they represent and how do they correlate as actors?

The hunt theme germinated for me in a fruitful rivalry between painting and photography. By comparison with the speed and dynamism of the snapshot, my pictures were deliberately slow and undynamic, the emphasis instead placed on a contrived compositional relation between simple components taken from an accessible pictorial vernacular of characters. A dog motif is repeated most often, functioning for me as signifier of prior (hunting) portraits, loyalty, senses such as smell and taste, and instinct – something arguably lost to humans. Regarding loyalty, I was thinking not only of pictures as loyal companions but also the activity of making them: a mostly solitary pursuit for the painter that provides a type of further being – beyond the self – to correspond with.

The distinctions and overlaps between painter, photographer and hunter were my first self-referential preoccupations. The painter has historically brought objects back to the studio, sometimes simply rendering them motionless, sometimes killing them – as per the suitably named still life – so that they can be slowly processed as painting. The photographer, by contrast, is closer to the hunter in so far as the capture of an image is a far more immediate and reflexive act, hence the term “photoshoot”. The photograph and the gunshot happen in the blink of an eye.

Recognising the possibly reactionary nature of a “return to painting”, I made paintings that intentionally negate a number of subjective motivations. In so doing I have used strategies from pop and conceptual art such as (a) repeatable mechanisation to recreate images; (b) an erosion of art and non-art boundaries through the use of an everyday-image vernacular (for example, clean colours that avoid notions of elevated expression, and simple illustrational type figuration); and (c) the use of appropriation to represent selected tropes of painting (mastery, gesture and authenticity to name the most obvious).

An ‘experience of meaning’

The figurative depiction, evoking how-to guides and children’s books, amounts to a style (or anti-style?) in keeping with the objective approach of conceptual art where art is simply information and subjective expression denied. How-to guides use images as language, in other words, as signs. I have no time for a “return to painting” that uses the alibi that human experience should be at the centre of art and that painting is uniquely equipped for such a task. My pictures are signs – but not simply signs. By not allowing the signifiers in my pictures to settle, my aim was to make possible the philosopher Peter Osborne’s phrase an “experience of meaning”: not so much a rational and linguistic interpretation of a sign, but an aesthetic sense between materiality and meaning. Aesthetic pleasure is sustained in the application of paint and notably nonrepresentational use of colour. Figure and ground relationships are also consistently confused through the use of a black outline that often overlaps and continues beyond the point where it makes spatial sense – in front of an object that is itself in front, for example.

Finally, the theme of absence runs throughout these images. I recognise its significance from earlier work where I employed the stencil as a type of mechanical means. Through such means, the artist – myself – can be at a remove from making the final painting: farewell to subjectivity, the task can effectively be “hired out”.

Although the particularities of these pictures do not make it wholly practical, there is, I would argue, an insinuation of the artist as absent. In How to Change a Lightbulb – Blue Chair (2016), and its Orange Chair companion, the camera is set up for a shoot, but where is the photographer, or indeed the subject? In Hiding (2016), the figure is in plain view “hiding” behind the grey paint. The same grey paint that renders the figure and ground as virtually flat, and the dog sightless. The idea of the “formless” is raised in this instance as both the figure/ground relationship and sight are cancelled by what is effectively a monochrome. However, two important (dog) senses (especially for detecting feet!) remain visible, namely nose (smell) and tongue (taste).

My art in the past has drawn on ideas from psychoanalysis, and inevitably issues such as voyeurism lurk behind my graphically rendered motifs here. Looking Through a Hole (2016) asks what it is to be watched yet unaware. And the viewer is left to unravel and construct the clues of these unexplained moments, narratives and objects caught in action with no resolve. As the gallery notes put it: “The pictures are laden with clues but interpretation is slippery and as elusive as the moment between waking and sleeping. While they hint at potential happenings these new paintings reveal no certainty of anything at all.”

| Creators | Cumberland, S. |

|---|---|

| Description | The research interrogates post-conceptual painting and repositions it as picture making. Stepping outside the parameters of painting as a medium, drawing on historical references and investigations of contemporary psychoanalysis, |

| Portfolio items | Sensible Signs: Pictures and Not Painting After Conceptual Art |

| The Painting Show | |

| Handmade Colour Pictures | |

| Year | 2016 |

| Publisher | University of Westminster |

| Keywords | Paintings, Postconceptual, Pictures. |

| CREAM Portfolio | |

| Digital Object Identifier (DOI) | https://doi.org/10.34737/qqqz8 |