Project narrative

The project was a response to the lack of recognition of the Jamaican contribution to the story of British popular music since the 1960s within the UK cultural establishment and academia – and the issues of identity, heritage and sense of belonging that have resulted within BME communities.

The approach I adopted, working closely with other members of the AHRC team, including Professor Les Back, Jacqueline Springer, Dr Caspar Melville, Janet Browne and Dr Chris Christodoulou, ensured that our key strategy to share knowledge and integrate the community with the academic research was realised through a series of key public events, meetings and seminars. Each member of the team developed their own inquiries, while I managed and coordinated the group, balancing our use of academic methodologies with the need to ensure public and community engagement.

In seeking to create a narrative through research outputs – in the form of an exhibition, a documentary film and an online resource – as a first step to redressing the balance, I had plenty of “raw material” to draw on: namely, the musical talent embedded in three generations of Britons of African-Caribbean origin. The challenge was to locate the musicians, recording artists, singers, MCs and record producers I wanted and involve them in the aims and objectives of the research leading to the film and exhibition.

In telling their story, however, I had to fight their fears of cultural appropriation, while challenging the continued erosion of their contributions to British popular music history. My position as an established artist – I’d been with the reggae band Steel Pulse, then a successful record producer working with Björk, Soul II Soul, Jamiroquai inter alia – helped me access hard-to-reach musicians, industry experts and community-based content spanning six decades.

Initiatives such as supporting participants to write their own stories, transcribing interviews and sharing the technology used to capture their content paid dividends – producing more than 200 images, 70 × 40-minute filmed interviews and a line-up of celebrity guests willing to participate in events allied to the Ambika P3 exhibition. It also paved the way for my initiation of the Grime Report.

My standing as a musician and record producer gave me access to artists. Involving them in the project, however, building an audience for the exhibition, required methodological innovation. Each artist has a potential audience, I figured, if only their family, and I used this approach to widen the network. Essentially, I applied techniques of participation I had learned from marketing and adapted these as a research method to secure their participation.

Curating the exhibition involved initiating other new connections between academic and community researchers. I incorporated ideas and concepts gleaned from a decade of small-scale community projects and funding applications into these methods. From the outset, the aim had been to produce a large-scale exhibition that would challenge major art spaces and museums. We also wanted to respond to the BME music community, who felt they were always a footnote in someone else’s story. As a practitioner active in the community, I had already acquired an in-depth understanding of the historical challenges. Positioning London’s Caribbean musicians as the critical resource and content-delivery mechanism was therefore critical. This approach, as evidenced in our audience evaluation survey, triggered heightened emotional responses, among both participants and visitors to the exhibition. Among participants, initial resistance to accessing their memories and artefacts was replaced by an enthusiastic desire to join in.

As well as drawing in the black community, many of whom would not normally go to an art gallery, I had to present an exhibition that would attract and get the buy-in of the museum and art world. I also wanted to go beyond music to highlight the influence of reggae on fashion and street style, and the live events allied to the exhibition (including one where the multi-generational audience was invited to dress as if they were going clubbing) enabled that to happen. Transformed into willing performers, the audience could view their culture and heritage in a new light.

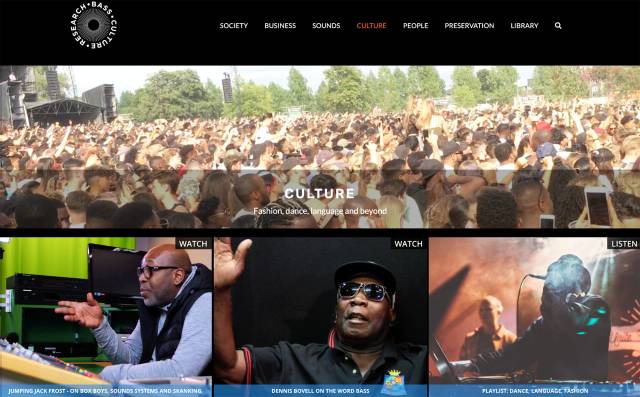

The Bass Culture website (basscultureduk.com) is the first online archive to record the historical contribution of black British artists to broader UK culture. It was constructed on a multimedia basis – visitors “watch” videos, “listen” to music, and “look” at photography – and, as a result of our research, was compiled using media split into the following areas of focus: society (socio-political context), people (the artists), sounds (contextualising the music within broader UK culture), culture (how the music inspired fashion, dance, language and more), business (historical industry contributions by those facilitating the artists) and preservation.

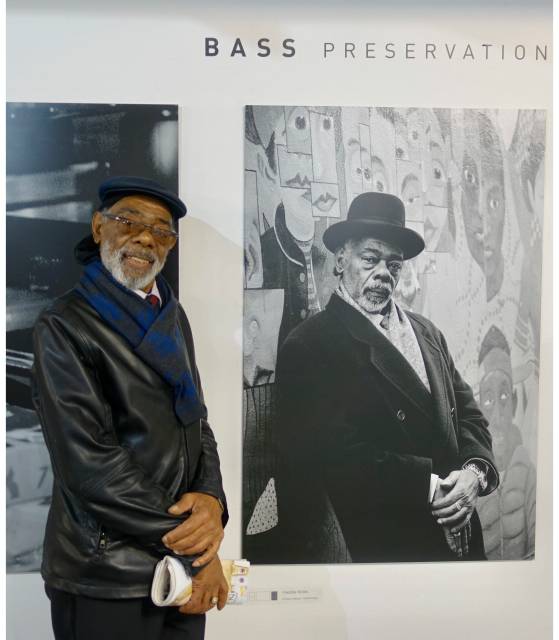

Bass Culture 70/50, a multimedia exhibition at Ambika P3, attracted 3,400 visitors. Ambika P3’s vast 14,000 sq ft exhibition space facilitated the reordering of the images, memories, music and film, previously disordered and made small by traditional accounts of British popular music history. My initial curatorial approach identified photography as the most appropriate medium, so 200 images (including Jamaican trombonist Rico Rodriguez, Count Prince Miller, Millie Small) were scaled up to larger-than-life size, instantly transforming their cultural impact, value and importance, according to the feedback from visitors. These were displayed in sections that drew on the same categories we had used on the website.

The exhibition also included paintings commissioned to capture for posterity hidden (yet iconic) sites, such as an early record shop specialising in reggae and its founders Duke and Chris Peckings, which saw the Museum of London and other institutions bidding to buy it.

Ultimately the scale of the exhibition produced significant budgetary and technical challenges. But this in turn prompted innovation and creativity from students and the team of volunteers that grew as the project developed, extending the intergenerational knowledge transfer for the duration of the project.

For the hour-long Bass Culture documentary film, made in partnership with Fully Focused, the aim was to be both informative and celebratory, delivering an unashamedly feelgood work that would bolster the black community’s pride in their musical heritage while conveying the finer points of sound-system culture via contributions from both early practitioners such as Jerry Power and young performers (Shola Ama, Paigey Cakey et al) who recall it as a phenomenon of their parents’ generation. In a fast-moving montage of clips to a pulsing reggae soundtrack, the comments of DJ/producers such as Jason Kaye and Jumping Jack Frost add gravitas to the proceedings.

| Creators | Riley, M. |

|---|---|

| Description | As P-I for the AHRC project Bass Culture (£533,032), Riley’s research involves locating, capturing and preserving memories, experiences and ephemera from three generations of musicians, music industry participants and audience members. The associated communities and networks have played a key role in transforming Britain into a multicultural society, yet their contributions have previously remained absent from the country’s cultural institutions. The output components draw on original interviews, new and archival imagery to inform both a large- scale multimedia, interdisciplinary exhibition at Ambika P3 (Bass Culture 70/50, 2018), and a collaboratively produced documentary film (Bass Culture, 2018). Included are a wide range of oral testimonies and previously unseen images (representing over 50 years of London-based content) that explore and make manifest reference points connecting the influence of British sound-system culture to modern and contemporary music, fashion and cultural forms today. Riley’s book chapter (2014) draws on his experiences as a black British musician of Jamaican heritage to contextualise the origins and emergence of black British music in the 1970s and 1980s against the socio-political backdrop of the era. Riley devised a methodology for working together with wide-ranging collaborators to break down and classify areas of interest, without disenfranchising the participants or co-researchers. In creating the online resource, the project’s researchers were able to apply key categories that helped guide navigation of the complex layers of material, cultural and economic activity underpinning key values that were shared within the community, while mapping the contribution for academia. The Bass Culture project successfully united academics, museums and the African Caribbean community in a series of projects that helped make visible the Jamaican contribution to British popular music and culture and lay the basis for popular music teaching that more accurately reflects that influence. |

| Portfolio items | Bass Culture film |

| Bass Culture 70/50 | |

| Basscultureduk.com | |

| Bass Culture: an alternative sound track to Britishness | |

| Ticket Master State of Play Grime Report | |

| Jazz Jamaica All Stars: The Trojan Story - Live Event | |

| Year | 2014 |

| Publisher | University of Westminster |

| Keywords | CREAM Portfolio |

| Digital Object Identifier (DOI) | https://doi.org/10.34737/qqvqz |