Project narrative

The research aimed to explore the thesis that central to the design, production and consumption of menswear in the UK is the reinforcement of a gendered hegemony of masculinities. Through the endless reiteration of archetypal garments and their functions, men’s dress codes and roles are prescribed and reinforced, thereby successfully enabling menswear to evade analysis and remain invisible.

Methods

The initial research in 2016 focused on the establishment of the Westminster Menswear Archive (WMA). The objective was to collect significant examples of menswear, with a focus on garments designed, produced or worn in the United Kingdom, as the basis for object-based research into this material culture and developing new knowledge. Some of the most important national dress collections within museums originated in significant donations from benefactors. For example, the Fashion Museum, Bath, was started by Doris Langley Moore, who gave her collection to the city in 1963. The Manchester Gallery of Costume at Platt Hall was based around a collection donated by Cecil Willett Cunnington and Phillis Emily Cunnington in 1947. Most museum collections of fashion and dress have been shaped by gendered ideas about clothing and fashion with significantly fewer acquisitions of menswear.

The WMA started without a donated core collection but with a large budget for acquisitions. Groves was therefore able to design a collection development policy that would focus on the underrepresented area of men’s fashion and men’s dress with an emphasis on British produced, designed or worn garments. In doing so, the team established a new approach that acknowledges the significant differences in the design processes, functionality and purpose of menswear, distinct from that of womenswear. They used online sales and auction sites as a means of researching and acquiring objects, primarily eBay. Ninety-nine different search alerts (the maximum possible) were set up, resulting in 99 emails daily for each specific term. This methodology ensured that the acquisition of objects covered the spread of cloth-based artefacts they wished the collection to contain.

The archive was deliberately conceived to exist between industry, the museum and the university. A purposely contested space that would enable it to examine the shifting relationship between these institutions previously highlighted by Breward in his paper ‘Between the museum and the academy: Fashion research and its constituencies’ (2008).

This research builds on increasing interest and development within the studies of masculinities and men’s fashion, for example, the International Encyclopedia of Men and Masculinities (Flood, 2007), The Men’s Fashion Reader (Karaminas and McNeil, 2009) and the establishment of the journal Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion in 2014. Over three years, the team researched, sourced and accessioned more than 1,700 artefacts into the collection, which would form the basis of its exhibitions.

The first exhibition, Archetypes (2015), identified the use of archives and pre-existing garments as a critical research and design process within contemporary menswear design. In comparison to the methods typically undertaken in the creation of womenswear, the design language of menswear predominantly focuses on the replication of functional and historical archetypal garments intended initially for specific industrial, technical or military use.

This finding informed Groves’ decision that the WMA would, therefore, be designed to be used also as a resource for external designers to undertake research, and to inform undergraduate and postgraduate students and their current design practice. Companies that have used the archive for this purpose since 2016 include Adidas, Alexander McQueen, CP Company, Daks, Dunhill, Hunter, Jigsaw, Burberry, Margaret Howell, Pringle, Rapha, Tom Ford, Umbro and Versace.

In summary, the method, approach and process of discovery led to:

- Creation of a new inclusive taxonomy of dress that embraces a parity between cloth-based objects.

- Establishment of a substantial new dress collection enabling a previously underresearched area of fashion history to be understood through object-based research.

- Creation of a significant contribution to the knowledge and understanding of the production, consumption and design of British menswear and its historical context.

- Development of new understandings of the role of garment archives in the design processes of contemporary designers.

- Broadening the understanding of menswear as a design discipline distinct from womenswear.

Testing hypotheses

Invisible Men (2019) built on the earlier exhibitions Archetypes (2015) and The Vanishing Art of Camouflage (2016); the latter included early artefacts acquired by the WMA. These smaller exhibitions allowed Groves to test the hypothesis regarding the inherent design methodology and distinctiveness within menswear: that military, industrial and ceremonial clothing informs the design language of menswear in a way that is not found within womenswear.

Invisible Men aimed to fully explore the multiplicity of relationships and dialogues between these object categorisations, and in doing so change historic exhibition narratives of fashion and dress that present menswear as being dominated by the figure of the dandy.

The title Invisible Men acknowledged the absence of menswear within dress collections and fashion exhibitions. It also references a distinctive method of design intrinsic to menswear and an inherent approach to male dress that is preoccupied with both unwritten rules and minor, almost unnoticeable detail. The exhibition design consciously reflected this through its regimental presentation, and the use of headless mannequins positioned all at the same height, echoing the hegemonic power of uniformed men that deliberately makes the individual invisible.

Groves decided to show a total of 186 objects displayed on 156 mannequins, making Invisible Men the biggest exhibition of menswear to have been staged in the UK. Planning for the exhibition started in June 2018 with initial curatorial selections of garments and themes. At this point it was decided only to exhibit objects from the permanent collection of the WMA, to underpin the research principles that had been developed within the collection. As the curatorial statement developed, the team was also able to acquire additional objects to develop the exhibition thesis. At this point, further research was initiated by contacting over 57 individual menswear companies in the UK, Japan, France, Italy, Germany, Sweden, and the United States, to research specific objects that would be displayed within the exhibition.

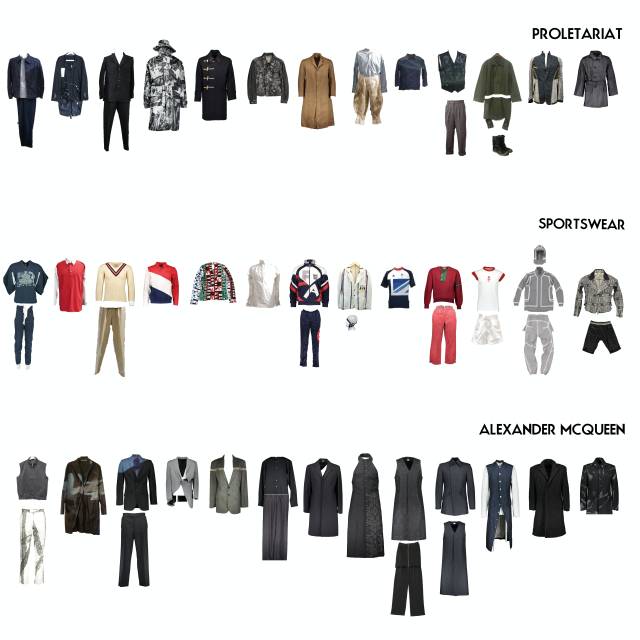

The final object list for the exhibition included items from 60 designers or other organisations and was divided into 12 thematic sections highlighting different aspects of menswear. Designer garments were displayed next to industrial and functional menswear. Central to the curation of the show was its location, sited three floors below ground in a vast 14,000sq ft industrial space, a former concrete testing hall. The rawness and redundancy of this space illuminated the fetishistic appreciation of the working man in all his heroic iterations (Bell, 2020).

The layout of the exhibition was designed through a series of plans, drawings and meetings focused on the 12 categories and the approach to collecting as developed by Groves and Sprecher. The final design was conceived to start with the simplest, least gendered garment, the cape. Then as each section progressed, the garments become more complex as their functionality increased. The final section devoted to ceremonial garments highlighted the endurance of specific types of clothing where their original functionality has become ornamental, historical and eventually redundant.

Each section was presented on 12 identical horizontal platforms. Mannequins were aligned in military formation to create 12 rows displaying 13 torsos, implying the manifestation of a subterranean army of invisible men. Viewed individually, each thematic platform could be considered as a selfcontained miniature exhibition. However, the regimental uniformity of presentation allowed the visitor to draw additional connections across these defined sections suggesting how the perceived rigidity of boundaries within menswear could merge, dissolve and disappear.

Through unique access to and knowledge of Alexander McQueen’s work, due to Groves’ role as his design assistant in the 1990s, the exhibition was able to present for the first time publicly significant examples of McQueen’s formative early menswear. This provided an opportunity to articulate how his approach to tailoring, learnt on Savile Row, underpinned both his menswear and womenswear collections. Central to this display was a selection of garments from his Autumn Winter 1998 collection, Joan, which explored ideas of gender identity and martyrdom, focusing on the language of tailoring and ecclesiastical garments. As it was adjacent to other sections within the exhibition, it allowed visitors to contextualise McQueen’s work with examples of early 20th-century military and religious tailoring.

The section devoted to camouflage visually interrogated its role as the epitome of heteronormative masculinity. The strong association of camouflage with the military allows for male reinterpretation of the dandy trope — the possibility of adorning menswear with a significant expanse of colour and pattern without undermining masculinity.

Conference, talks and presentations

Coinciding with the exhibition, Groves hosted several events for academics and wider audiences:

- A one-day conference, with eight invited speakers drawn from leading menswear scholars in academia and industry practitioners, saw 120 delegates explore the core issues raised by the exhibition.

- At the same time, a series of weekly In Conversation events featured a variety of prominent menswear designers being interviewed by journalists in front of an audience of 140 guests.

- A series of special events saw delegates from organisations including the British Fashion Council, Première Vision Paris and the National Saturday Club being given private curators tours.

- Supplementing the main exhibition at Ambika P3, a satellite exhibition featuring additional objects from the archive was shown for two weeks at 18 Montrose in Kings Cross, London

| Creators | Groves, Andrew |

|---|---|

| Description | Groves led the project to establish and launch the WMA in 2016, with the purpose of redressing the historical omission |

| Portfolio items | Invisible Men: An Anthology from the Westminster Menswear Archive |

| Invisible Men Conference | |

| Invisible Men: An Anthology from the Westminster Menswear Archive | |

| Year | 2019 |

| Publisher | University of Westminster |

| Web address (URL) | https://www.invisiblemenexhibition.com/ |

| Keywords | CREAM Portfolio |

| Digital Object Identifier (DOI) | https://doi.org/10.34737/qqq4v |